Choral is a language for programming choreographies. A choreography is a multiparty protocol that defines how some roles (the proverbial Alice, Bob, etc.) should coordinate with each other to do something together.

You can use Choral to program distributed authentication protocols, cryptographic protocols, business processes, parallel algorithms, or any other protocol for concurrent and distributed systems. At the press of a button, the Choral compiler translates a choreography into a library for each role. Developers can then use your libraries to make sure their programs (e.g. clients and services) follow your choreography correctly—see Choral’s methodology. Choral makes sure that your libraries are compliant implementations of your choreography, makes you more productive, and prevents you from writing incompatible implementations of communications—see Choral’s advantages.

Choral is interoperable with Java and we plan on extending it to support other languages in the future. Choral is compatible with Java in three ways:

- its syntax is a direct extension of Java (if you know Java, Choral is just a step away);

- you can reuse Java libraries in Choral code;

- the libraries generated by Choral are in pure Java with APIs that you control, and can be used inside of Java projects directly.

For now, Choral is a prototype. The language is part of an ongoing research project (see the about page) and future releases might break backwards compatibility. However, Choral is already usable for early adoption and teaching. If you’re curious, you can try it out yourself and get in touch with us!

Explain it like I’m 5!

The problem

Programming distributed systems gives you headaches because you need to figure out how to correctly coordinate multiple programs that interact via side-effects, which you need to manually control (send/receive over channels). If you made some mistakes, finding what went wrong is even harder, because you have to figure out all the possible sequences of communications that can happen (and go wrong) during the concurrent execution of your programs. Testing is hell, as it requires the integration of many distributed components, mocking, etc.

Choral

Choral relieves some of those headaches because you can write as a single program, the whole coordination (protocol) that you want your distributed system to follow. Choral is also friendly to Java programmers (and close to C++, C#, Kotlin, Swift, etc.) because it extends its syntax with a new kind of (higher-kinded) types to let you express things like “the Client communicates this to Service, then Service communicates that to the Login Provider, then […]”. In practice, Choral wraps the headache-mongering side effects used to implement communication within type-safe abstractions, so you can concentrate on the high-level details of the implementation.

If you introduce some incompatibilities between the description of how you want your programs to coordinate and how you actually implemented it, like expecting data at a participant but forgetting to communicate it, the Choral compiler reports you that error and helps you solve it. Moreover, Choral comes with a testing tool (ChoralUnit) that helps you write integration tests with the simplicity of unit tests, performing for you the runtime (integration) tests on your distributed system.

In essence, you program with the simplicity of plain old sequential programs, but you get distributed systems with decentralised control with strong correctness guarantees. This allows you to use or distribute them with a higher level of confidence. You can also reliably compose different Choral(-compiled) programs, to mix different protocol and build the topology that you need.

Language

If you just want to glance at how a Choral program looks like, you can jump to Alice, Bob, and Carol go to a meeting and then come back here for the details.

Choral is an object-oriented language with a twist: Choral objects have types of the form T@(R1, ..., Rn), where T is the

interface of the object (as usual), and R1, ..., Rn are the roles that collaboratively implement the object. (Technically, Choral data types are higher-kinded types parameterised on roles, which generalise ideas previosly developed for choreographies and multitier programming; more on that at the end of this page.)

Incorporating roles in data types makes distribution manifest at the type level. For example, we can write a simple program that prints hello messages in parallel at two roles Alice and Bob.

class Hellos@(Alice, Bob) { // A class of objects distributed over two roles, called Alice and Bob

public static void main() {

System@Alice.out("Hello from Alice"@Alice); // Print "Hello from Alice" at Alice

System@Bob.out("Hello from Bob"@Bob); // Print "Hello from Bob" at Bob

}

}

Class Hellos is not very interesting, because Alice and Bob do not interact.

Interaction is achieved by invoking methods that can “move” data from one role to another, like the com method of interface SymChannel.

We give a simplified view of this interface below—see the details in the documentation of channels.

// A bidirectional communication channel between two roles A and B

interface SymChannel@(A, B) {

public void <T> T@B com(T@A mesg); // given data of type T at A, returns data of type T at B

/* more methods, not shown here... */

}

Choral does not fix any middleware: as long as you can satisfy the types of the choreography that you are writing, you can use your own implementations of communications and existing Java code in Choral. The Choral type system forces you to specify the communication requirements of your choreographies explicitly (channel topology, type of transmissible data, etc.).

Using channels, we can write more interesting choreographies, as we can see in the next example.

Alice, Bob, and Carol go to a meeting

Alice calls Bob to ask if they could have a meeting with Carol on some topic.

Bob wants to know whether Carol could go first, so he asks her. If she can go, then he considers it himself. In the end, Alice needs to know the final result on whether the meeting can take place from Bob.

We can define this protocol as the class below. Note that Choral borrows the forward chaining operator >> from F#: in the following, expression >> object::method means object.method(expression).

class MeetingVote@(Alice, Bob, Carol) {

public static Boolean@Alice run(

SymChannel@(Alice, Bob)<Object> chAB, // A bidirectional channel between Alice and Bob that can transfer objects

SymChannel@(Bob, Carol)<Object> chBC, // A bidirectional channel between Bob and Carol that can transfer objects

String@Alice topic, // Alice's topic for the meeting

Predicate@Bob<String> bobsPredicate, // Bob's predicate to decide whether he could go

Predicate@Carol<String> carolsPredicate // Carol's predicate to decide whether she could go

) {

String@Bob x = topic >> chAB<String>::com; // Alice's topic is communicated to Bob

Boolean@Bob carolsChoice =

x // Bob's copy of the topic..

>> chBC<String>::com // ..is communicated to Carol.

>> carolsPredicate::test // Then Carol decides whether she wants to go..

>> chBC<Boolean>::com; // ..and communicates it to Bob.

// Now Bob considers going only if Carol goes, and communicates the decision to Alice.

return (carolsChoice && bobsPredicate.test(x)) >> chAB<Boolean>::com;

}

}

Development Methodology (or: what Choral does)

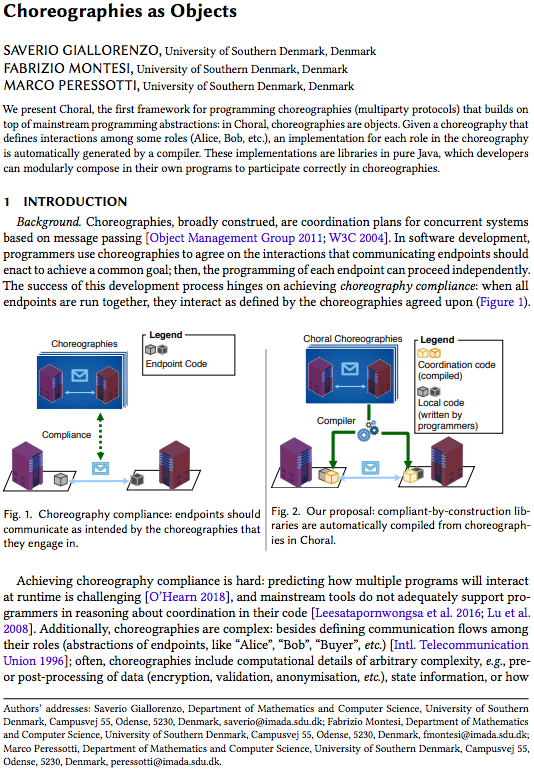

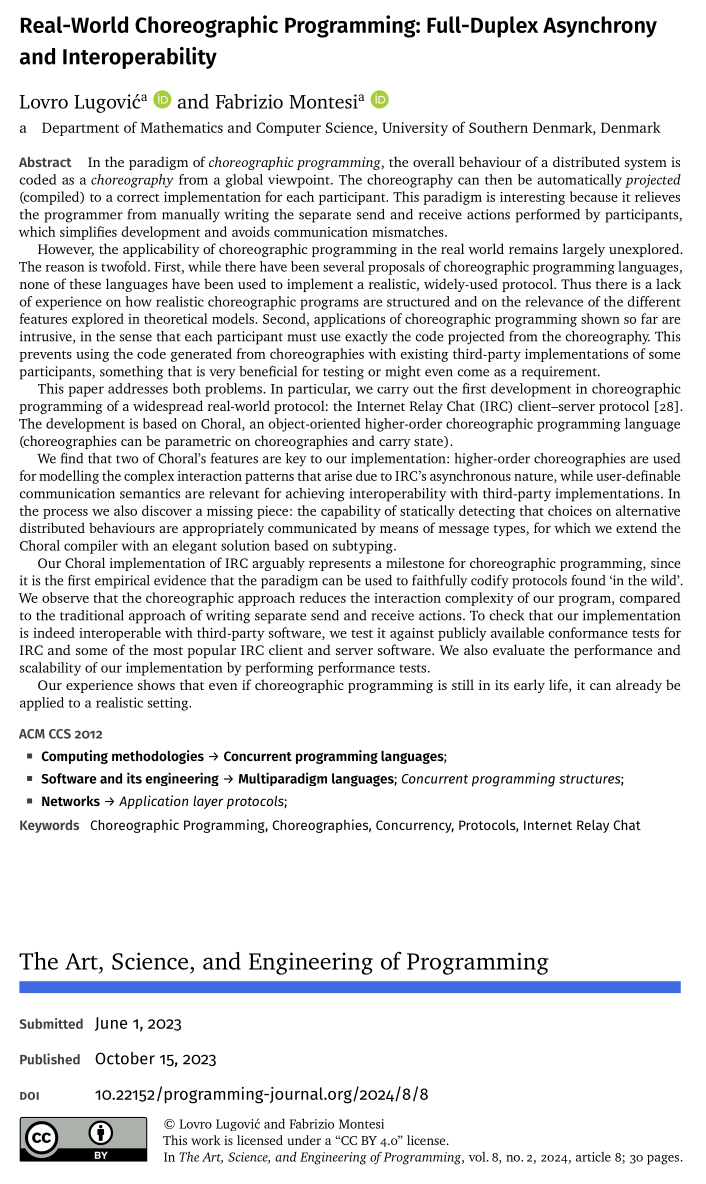

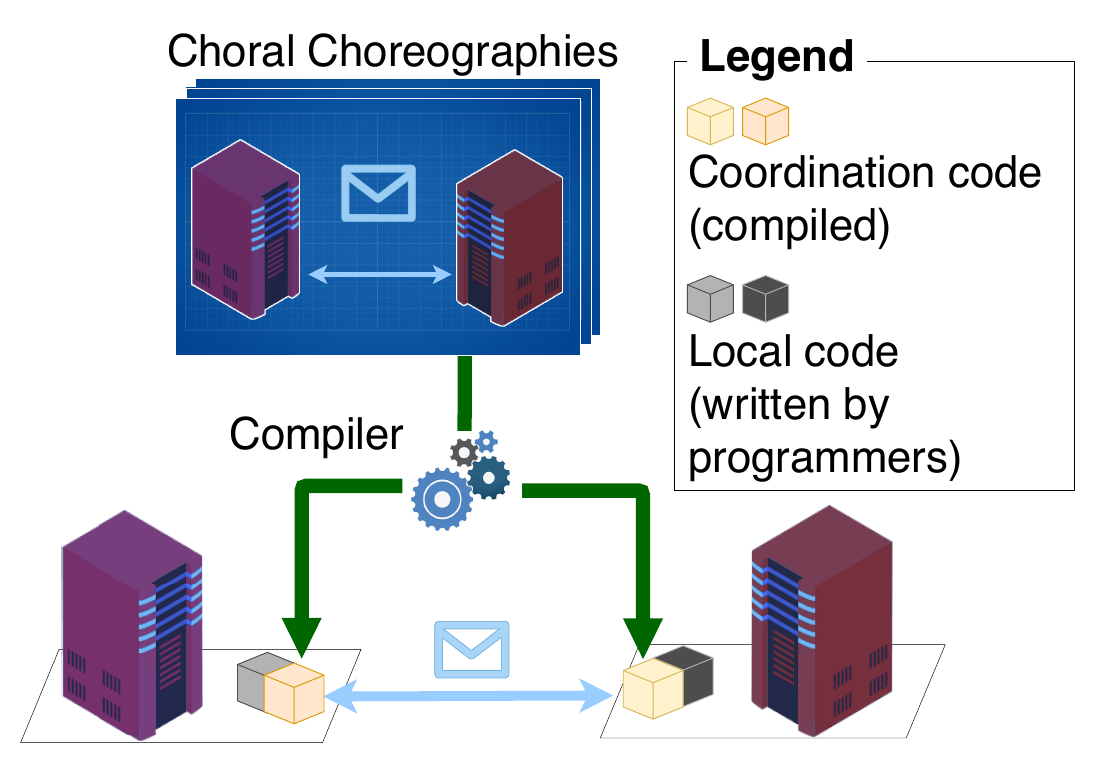

Choral is designed to generate correct implementations of choreographies as Java libraries. In Choral’s development methodology (figure above):

- the intended coordination that a system should follow is written as a Choral choreography;

- then, the Choral compiler generates a Java library for each role defined in the choreography;

- finally, programmers can use these libraries in their own local implementations of each system participant (a service, a client, an actor, etc.).

For example, given a choreography like the one above for the roles Alice, Bob, and Carol, the Choral compiler generates a Java library for each role.

Each library offers an API that the programmer can use inside of their own project to participate in the choreography correctly within a concurrent/distributed system.

Let’s have a look at the code that would be generated for Alice’s Java library.

class MeetingVote_Alice {

public static Boolean run(

SymChannel_A<Object> chAB, // Alice's end of her channel with Bob

String topic // Alice's topic for the meeting

) {

chAB<String>.com(topic); // Alice sends her topic to Bob

return chAB<Boolean>.com(); // return what is received from Bob

}

}

Notice that all code that has nothing to do with Alice from the choreography has disappeared. In other words, Alice does only what pertains her.

A Java developer can now import MeetingVote_Alice and invoke method run to coordinate correctly with third-party implementations of Bob and Carol.

This was a simple example. Wanna see something more realistic? Jump to our documentation.

What advantages does Choral bring?

- Choral saves you time. In our first use cases, Choral reduced the lines of code that we had to write to implement choreographies from 50% up to almost 400%.

- Choral makes your coordination code safer.

- Its compiler takes care of implementing the local behaviour of each participant for you. Implementing correct local behaviour manually is hard.

- It prevents entire classes of errors in the implementation of a choreography, like distributed programs performing incompatible communication actions and wrong pre-/post-processing of data. Furthermore, code generated by Choral is guaranteed not to introduce deadlocks (deadlock-freedom).

- It gives you a global view on how roles coordinate with each other, so spotting inconsistencies is easier.

- You retain control of your library APIs: the method signatures of the compiled Java libraries are homomorphic to (they resemble the structure of) those in the source choreography. Essentially, what you see is what you get.

We think that Choral has the potential to be especially relevant for business processes, microservices, security protocols, and distributed services in general.

Articles

Choral

If you’re interested in programming languages, want to know more about how Choral works and how it relates to other works, please refer to the article Choral: Object-oriented Choreographic Programming. Choral is a choreographic programming language. You can read more about choreographic programming on the Choreographic Programming Wikipedia article, the PhD thesis that introduced choreographic programming, or the introductory textbook to theory of choreographic languages.

Ozone

Ozone is an experimental library that lets you safely use futures in your Choral code. With Ozone, you can write endpoint code that handles requests in parallel or returns values asynchronously (e.g. via a CompletableFuture). You can learn more about Ozone by watching this video or by reading the research article Ozone: Fully Out-of-Order Choreographies.

Real-World Choreographic Programming

Real-World Choreographic Programming: Full-Duplex Asynchrony and Interoperability carries out the first development of a widespread real-world protocol – Internet Relay Chat (IRC) – using Choral, tackling the issues of full-duplex asynchrony and interoperability.